Spacetime

In his “Spacetime” installations, Benjamin Johnson offers works that are unified by glass but that relegate the material ancillary to paper and light.

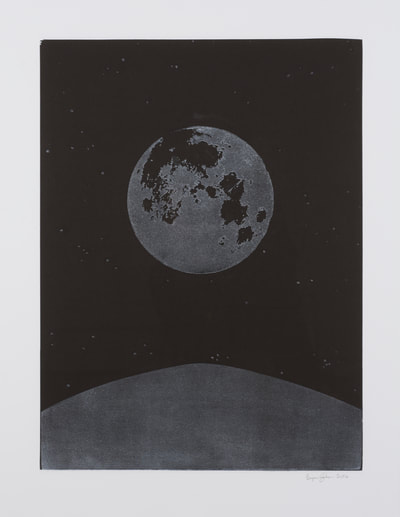

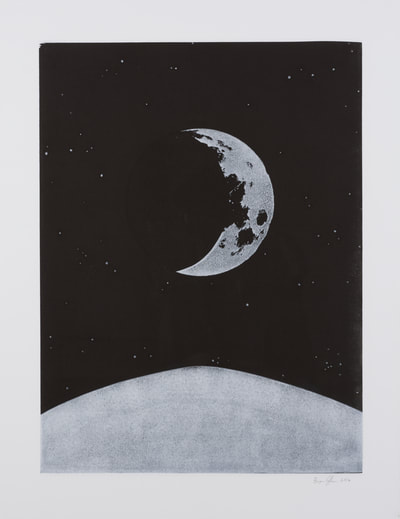

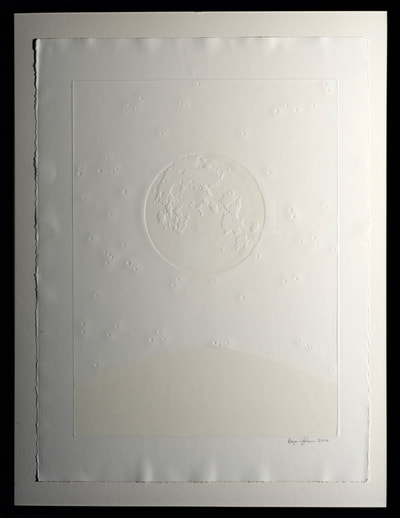

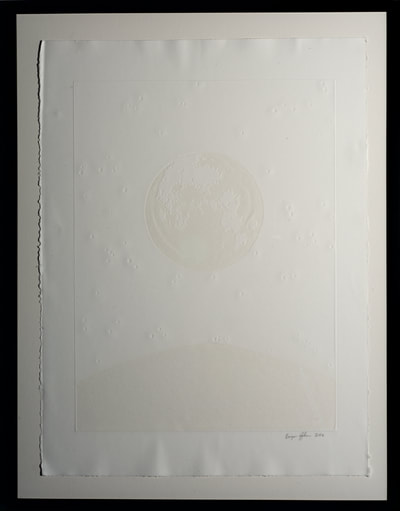

Installed in the main gallery of IMoCA’s CityWay space, Johnson’s prints collectively show the moon’s changing phases. A representation of perspective, the artist deliberately shows the curve of the Earth at the lower edges of his multiples. This is a reminder that the phases[1] are phenomena, a function of perceived reflected sunlight. Johnson furthers this idea through the prints’ shallow embossing of white paper that only resolves into imagery through contrasts of light and shadows heightened by directed spotlights. In his seven Reflecting Timepiece embossings, the lunar terrain remains present as a constant, an actuality, and areas of lunar phases are represented by barely perceptible, white printed ink. Still, the moon is known across cultures for its archetypal mutability as exemplified by Shakespeare’s famous “O, swear not by the moon, th' inconstant moon, That monthly changes in her circle orb.”[2] With more conventional depictions of the shadow, the five stages of Johnson’s inked Dark Sense of Time works represent this common perception of inconstancy.

Johnson’s prints remind us that not only is perception a matter of perspective, but that because moonlight is reflected sunlight, we experience the moon not as the thing itself but only as an index of the sun. It’s fitting that the source for the prints is similarly “hidden” and understood only by entering a rear gallery housing the vitreographic matricies. While the embossed-paper images can seem elusive and subject to conditions of light, the thick cut-and-etched glass pieces have physicality and presence. Displayed with light projected through them, they read as another kind of index of light—photographic glass-plate negatives.

Helpful for understanding the paradoxes in Johnson’s works, another glass artist, Koen Vanderstukken, considers in his text, Glass: Virtual, Real (2016), many of the dualities that glass presents. In one instance he writes, “Glass is always contradicting itself. There is often a stark contrast between its physical presence and its virtual absence, its physical density and its visual lightness, its perception as real and its virtual appearance.”[3]

At IMoCA Fountain Square Johnson offers a very different kind of meditation on reflected light. Situated in a street-facing display window, Visual Space Misperception, (like the moon) has very different expressions in the day and night.

[1] Scientifically speaking, “glass” is no longer considered a material in itself, but as a “phase” or “state” of matter in which a liquid is quickly cooled so that it does not crystalize. For further explanation see Koen Vanderstukken, Glass: Virtual, Real (London: Black Dog Publishing, 2016), 167-187. Whether discussing the moon, matter, or printmaking, “phases” or “states” refer to a considered moment with the potential for change.

[2] William Shakespeare, Romeo and Juliet, Act 2, Scene 2.

[3] Vanderstukken, 61.

Composed of dozens of hand-pulled glass canes, the installation seems in daylight as a contemplation of liminality especially as the hollow canes read as yellow-tinged but otherwise clear tubes. At night, the canes emit a ghostly green photoluminescence caused by recessed ultraviolet (black) light exciting uranium pigments. Johnson sets up a paradox in which the tubes have, to borrow Vanderstukken’s language, a “physical presence and visual absence” by day, and conversely a physical absence and visual presence by night. Because of variations in pigmentation and light intensity, the canes read as painterly stripes. While fluoresce is the “point” of black UV lights, Johnson puts to use the greater spectrum of the lights’ emissions, including the visible blue, indigo and violet set as a sensual contrast to the hyper-green rods. Johnson strategically directs light, creating pockets of intensity in which the fluorescent forms can seem concentrated, especially in contrast to the more fleeting luminescence at the installation’s periphery. Sustained gazing at the work “reveals” color variations as the eye perceives purple pools among the deep blues. All of this is calculated to induce ontological uncertainty—is what one sees actually “there” as physical object or ocular effect? As Johnson’s glass canes bow, some more than others, they create subtle disruptions in the vertical pattern, and cane, light and retinal ghosts combine to activate the work into ever-shifting moiré patterns and perceived kinetics. Vanderstukken posits that the optics of transparent glass are understood as the “unreal image of the real object—in other words a virtual object”[1] meaning that glass itself is often not comprehended by viewers except as optical distortions of the glass’s context. In Visual Space Misperception Johnson heightens the illusory in part to emphasize glass’s intrinsic virtuality.

Both Johnson (in his artworks) and Vanderstukken (in his text) hope to explode the conventional (material) understandings of this medium. Just as Vanderstukken posits that glass is “between materiality and immateriality, between being and nonbeing, between reality and virtuality.”[2] Johnson proffers “glass” works in which glass is not only paradoxical but attendant to paper and phenomena.

William Ganis

[1] Vanderstukken, 61.

[2] Vanderstukken, 193. Johnson’s works were made some months before the publication of this text.

In his “Spacetime” installations, Benjamin Johnson offers works that are unified by glass but that relegate the material ancillary to paper and light.

Installed in the main gallery of IMoCA’s CityWay space, Johnson’s prints collectively show the moon’s changing phases. A representation of perspective, the artist deliberately shows the curve of the Earth at the lower edges of his multiples. This is a reminder that the phases[1] are phenomena, a function of perceived reflected sunlight. Johnson furthers this idea through the prints’ shallow embossing of white paper that only resolves into imagery through contrasts of light and shadows heightened by directed spotlights. In his seven Reflecting Timepiece embossings, the lunar terrain remains present as a constant, an actuality, and areas of lunar phases are represented by barely perceptible, white printed ink. Still, the moon is known across cultures for its archetypal mutability as exemplified by Shakespeare’s famous “O, swear not by the moon, th' inconstant moon, That monthly changes in her circle orb.”[2] With more conventional depictions of the shadow, the five stages of Johnson’s inked Dark Sense of Time works represent this common perception of inconstancy.

Johnson’s prints remind us that not only is perception a matter of perspective, but that because moonlight is reflected sunlight, we experience the moon not as the thing itself but only as an index of the sun. It’s fitting that the source for the prints is similarly “hidden” and understood only by entering a rear gallery housing the vitreographic matricies. While the embossed-paper images can seem elusive and subject to conditions of light, the thick cut-and-etched glass pieces have physicality and presence. Displayed with light projected through them, they read as another kind of index of light—photographic glass-plate negatives.

Helpful for understanding the paradoxes in Johnson’s works, another glass artist, Koen Vanderstukken, considers in his text, Glass: Virtual, Real (2016), many of the dualities that glass presents. In one instance he writes, “Glass is always contradicting itself. There is often a stark contrast between its physical presence and its virtual absence, its physical density and its visual lightness, its perception as real and its virtual appearance.”[3]

At IMoCA Fountain Square Johnson offers a very different kind of meditation on reflected light. Situated in a street-facing display window, Visual Space Misperception, (like the moon) has very different expressions in the day and night.

[1] Scientifically speaking, “glass” is no longer considered a material in itself, but as a “phase” or “state” of matter in which a liquid is quickly cooled so that it does not crystalize. For further explanation see Koen Vanderstukken, Glass: Virtual, Real (London: Black Dog Publishing, 2016), 167-187. Whether discussing the moon, matter, or printmaking, “phases” or “states” refer to a considered moment with the potential for change.

[2] William Shakespeare, Romeo and Juliet, Act 2, Scene 2.

[3] Vanderstukken, 61.

Composed of dozens of hand-pulled glass canes, the installation seems in daylight as a contemplation of liminality especially as the hollow canes read as yellow-tinged but otherwise clear tubes. At night, the canes emit a ghostly green photoluminescence caused by recessed ultraviolet (black) light exciting uranium pigments. Johnson sets up a paradox in which the tubes have, to borrow Vanderstukken’s language, a “physical presence and visual absence” by day, and conversely a physical absence and visual presence by night. Because of variations in pigmentation and light intensity, the canes read as painterly stripes. While fluoresce is the “point” of black UV lights, Johnson puts to use the greater spectrum of the lights’ emissions, including the visible blue, indigo and violet set as a sensual contrast to the hyper-green rods. Johnson strategically directs light, creating pockets of intensity in which the fluorescent forms can seem concentrated, especially in contrast to the more fleeting luminescence at the installation’s periphery. Sustained gazing at the work “reveals” color variations as the eye perceives purple pools among the deep blues. All of this is calculated to induce ontological uncertainty—is what one sees actually “there” as physical object or ocular effect? As Johnson’s glass canes bow, some more than others, they create subtle disruptions in the vertical pattern, and cane, light and retinal ghosts combine to activate the work into ever-shifting moiré patterns and perceived kinetics. Vanderstukken posits that the optics of transparent glass are understood as the “unreal image of the real object—in other words a virtual object”[1] meaning that glass itself is often not comprehended by viewers except as optical distortions of the glass’s context. In Visual Space Misperception Johnson heightens the illusory in part to emphasize glass’s intrinsic virtuality.

Both Johnson (in his artworks) and Vanderstukken (in his text) hope to explode the conventional (material) understandings of this medium. Just as Vanderstukken posits that glass is “between materiality and immateriality, between being and nonbeing, between reality and virtuality.”[2] Johnson proffers “glass” works in which glass is not only paradoxical but attendant to paper and phenomena.

William Ganis

[1] Vanderstukken, 61.

[2] Vanderstukken, 193. Johnson’s works were made some months before the publication of this text.